We hear about the yoga sutras, Patanjali, and the eight limbs of yoga all the time.

Yoga teachers like to reference them throughout yoga classes and yogis just returning from a life-changing trip to India often scoff at the idea of yoga being limited to a physical asana practice because what-about-the-other-seven-limbs-of-yoga-psh.

But what the heck are they even referring to? And is it really as important as they make it out to be?

The quick answer is yes.

Yoga is an ancient practice that is treated like a science in India and around the world. It’s a guide on how to live a well-rounded, meaningful life and it’s the answer to most whatarewedoinghere questions.

It’s not the law (though many Indians have tried to make it so) and it’s not as shame-based as the 10 commandments. But the path of yoga works in a pretty similar way as both.

It’s more like, hey, if you want to feel good, do these things (ie asana, meditation, breathing exercises) and maybe don’t do these things (ie succumb to lust and desire on a whim).

Just like if you want to go to a restaurant to the south, don’t head north. That kinda thing.

And the teachings of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras helped put all of these concepts together in one comprehensive, helpful manual.

So What is Yoga, Anyway?

Yoga comes from the sanskrit word yuj, meaning to unite, come together or yolk. It’s a union of body, mind, and soul with a universal consciousness.

This union between ourselves and the divine is always there; it is part of our essential nature.

But sometimes life happens and we become distracted, disconnected from the universal consciousness and sucked in by our modern day societal demands. Next thing you know, our ego develops into a noisy, needy, and greedy energy monster, identifying with these distractions and disconnecting us from our consciousness.

The practice of yoga, then, helps us to keep that divine connection, to on the path of spiritual development.

Yeah, that is the point of yoga. Not to contort your body into (albeit sexy) poses.

You could be forgiven if the word yoga musters up images of expensive yoga pant-clad women contorting themselves in mat-to-mat yoga studios. It’s basically all that anyone talks about in the West.

The reality is that asana, the physical postures that have become the main focus of yogis in the West, is just one aspect of Patanjali’s eightfold path. (I sound just like a yogi come back from India, now, don’t I?)

Good. Because that’s where yoga came from, too.

To get to the roots of yoga we need to look no further than Patanjali’s yoga sutras.

What Are Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras?

The yoga sutra is a succinct but complete manual of Raja Yoga, meaning royal yoga. Raja Yoga is an ancient yogic science of controlling all of the senses through the mind and serves as the foundation of all yoga as we know it today.

The yoga sutra is like the yoga bible of the original yoga.

Patanjali was not the creator of Raja Yoga but merely the first known to systematize it in this bible-like text. The yoga sutra is considered one of the primary books of Raja Yoga and the foundation for most forms of modern yoga.

It is believed to be written as far back as 5000 BC and 300 AD. Yeah, ancient yoga texts is not an exaggeration.

The Sanskrit word, sutra, means thread. Each sutra is interconnected like beads on a thread, each bead being of equal importance. Patanjali’s manual is made up of 196 sutras in four chapters.

The practice as codified by Patanjali is called Ashtanga Yoga. This is not the Ashtanga Yoga as taught by Pattabhi Jois at the KPJAYI yoga institute in Mysore, India. That’s a specific style of yoga asana that has been branded, but not what Patanjali was originally referring to.

What Patanjali meant was a little more literal.

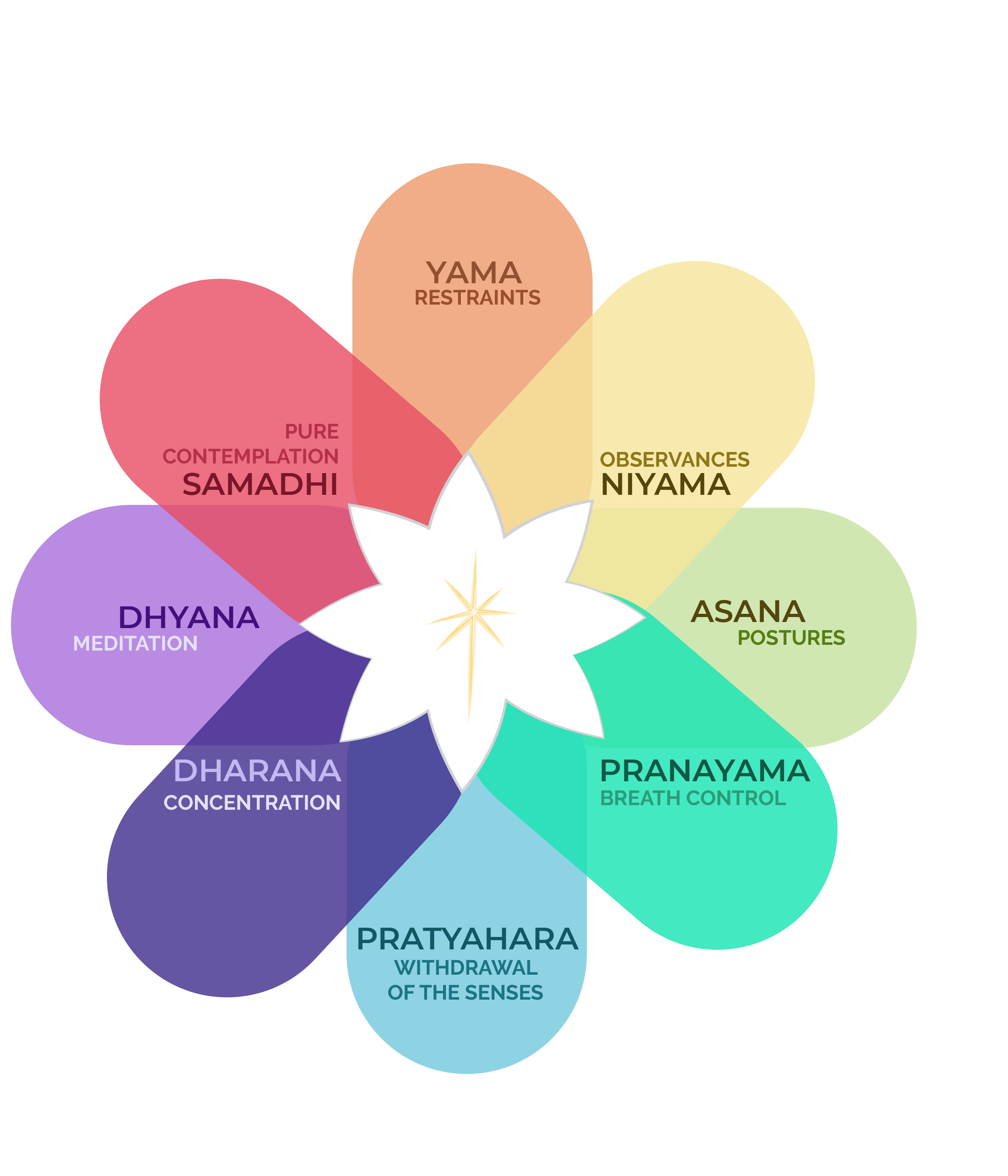

Ashta is the Sanskrit word for eight and anga translates to limb, fold or part. Patanjali’s yoga sutras describe an eight-fold path to help cultivate a life of meaning and purpose.

In just the second sutra, Patanjali defines yoga as yogas chitta vrtti nirodhah – yoga is the cessation of the thoughts in the mind.

Chitta is the place in our mind where our thoughts reside and vrtti is the modification of this. It is the development of our thoughts that creates a want or desire and brings us out of our natural state of peacefulness.

Yoga helps remove those wants or desires to bring us back to peace.

I mean, that’s a whole lot more than a few sun salutations and chair pose.

What are the Eight Limbs of Yoga?

1. Yama – restraints

The yamas are social conducts which are all about creating harmony between yourself and the external world. These universal principles don’t sound too different from morals we are taught as children, however following them completely requires a little more than ‘do unto others as you would have them do to you’.

They are basically the yogi’s commandments. A lot of people wonder if yoga is a religion and in a lot of ways it is. It guides us on how to be better people and basically gives us an instruction manual, starting with the yamas.

Ahimsa, the first yama, can be interpreted as non-violence, but not just physical violence. This means doing everything through the eyes of love and compassion. We practice non-violence through our thoughts, words, and actions.

Satya means truthfulness. This means not telling lies and is very good for our spiritual path. Speak the truth and come from a place of honesty, always.

In a society of ‘fake news’ and lack of transparency, the value of this yama doesn’t need much explanation and is certainly something we can all strive for.

The third yama is asteya, which means non-stealing. This covers all manners of stealing, not just the things we can hold in our hands. Wrongfully winning a race or coming top in the class falls under stealing, steya.

Intellectual property, be it lyrics, ideas, images or words should also be respected and not stolen. We can practice this through originality in our own actions, as well as giving credit when quoting or using someone else’s work. So bear in mind next time you’re reposting an image on social media or telling a joke as if it were your own!

Brahmacharya, is a yama that brings up some questions for the modern day yogi. The original translation of brahmacharya is most likely celibacy and yoga would not be the first philosophy to promote this.

This doesn’t mean you have to throw in the towel just yet though as many interpret it as simply living a virtuous life, sex included. Indeed for monks, brahmacharya means abstaining from any sexual activity. For most of us it means practicing self-control by not overindulging in the senses or letting them pull us one way or another.

The final yama, aparigraha is non-greed or non-coveting. One way of practicing this is only owning what you really need and not wanting more, be it multiple houses, cars or clothing.

Sometimes this is interpreted as non-jealousy, which seems to have been a human affliction since the beginning of time.

Monkey see, monkey want!

While it’s hard to prevent these thoughts from arising, we can strive to become aware of the green-eyed monster when it arrives by observing our thoughts for what they are and then letting them pass.

You might also like: The Meaning Behind The Top 9 Yoga Symbols (Before You Tattoo Them On Your Body)

2. Niyama – observances

The niyamas make up a personal conduct. The word niyama is also used in modern day Hindi for rules and regulations.

Saucha, the first observance, translates as purity or cleanliness. This applies to both the body and mind. Physically this can be as simple as our hygiene and diet.

Mental cleanliness is equally as important and requires the same consistency, whether coming to the mat for meditation, checking in with our thoughts or journalling.

Santosha is the practice of being content with what we have and where we are at the moment. These days, we are constantly bombarded with wants, needs and desires.

We want the latest device and the latest outfit and the latest thing as fast as the push notification reaches our phones. It’s no wonder that many of us live in a permanent state of dissatisfaction, always wanting more!

Taking moments of gratitude, whether silently in our heads or keeping a gratitude journal, helps root us in the present moment and bring us back to the innate truth that everything we have as it is now is enough.

The concept of tapas is commonly interpreted as penance or discipline. By regularly coming to the mat for yoga and meditation we establish discipline and structure, which provide the foundation for accepting and adjusting ourselves to what is coming into our path.

Svadhyaya is the niyama of spiritual study as well as study of the self. Study of sacred scriptures, such as Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra, the Bhagvad Gita, the Vedas or even the bible provide food for our intellect, which can later provide perspective for self-reflection.

The final niyama is ishvara pranidhana, meaning surrendering to the God, or supreme. This doesn’t have to mean a God in the sky or a particular deity, more that there is a universal, supreme power beyond all of us. By shunning the ego, we can surrender our actions and deeds to something that is much greater than ourselves.

The yamas and niyamas combined can be referred to as dharma mittra, the ethical precepts that make up the first and second limbs of Patanjali’s eight-fold path. They aren’t so different to the principles of any theosophical society and are the foundation upon which we build a purposeful life according to yoga.

3. Asana – physical postures

Most modern-day yogis might be surprised to know that out of all 196 sutras, asana is mentioned only once. Asana refers to physical postures, as well as your seat or the thing you are sitting on.

Sthira sukhamasanam is the stability and ease that is asana. This might sound like a far cry from the images of modern yogis tying themselves in complicated knots, but when we reflect on the goal of yoga being union, it becomes clear that asana is merely a tool to prepare the body to sit for long meditation.

Yup. Your asana practice is designed to help you sit still.

These days, we live such sedentary lifestyles, whether commuting to work, sitting at a desk, or on the couch. Our bodies are much more stiff and less agile than our ancestors’ and so we are less comfortable and unable to sit still for long periods of time.

Asana helps with that.

The physical postures of Hatha Yoga prepare the body for sitting by making the body more supple and by stimulating the systems to expel toxins caused by our modern diet and lifestyle.

It also plays an important role in preparing our bodies for the following limbs.

You might also like: 10 Yoga Terms That Every Yogi Must Know (Yes, Even You!)

4. Pranayama – breathing exercises

Pranayama is the practice of controlling prana, our vital life force. In Chinese medicine (TCM), this is referred to as qi. Ayama means expansion or control and through the practice of pranayama breathing we can increase the flow of prana in our bodies.

The connection between breath and mind goes both ways. While our emotions and mental state can affect our breath, we can also affect our mind through pranayama breathing exercises, like breath of fire or ujjayi breath. These exercises relax the mind by stimulating the rest-and-digest response and by nourishing every cell in the body with fresh oxygen.

The sutras on pranayama explain the breath should be observed and controlled in terms of place (desa), time (kala) and count (samkhya). We observe the breath in different parts of the torso, control the time we hold the breath and, the count of the breath through how long each inhalation and exhalation is.

My favorite breathing exercise is breath of fire, which I practice regularly to keep my mind sharp and my energy levels up.

5. Pratyahara – sense withdrawal

The fifth limb marks the bridge between the physical, external practices and the internal, more subtle practices of yoga. Pratyahara is about withdrawing from external senses and turning our focus inwards toward our emotions and consciousness.

The most common example is Yoga Nidra, the psychic or yogic sleep. You receive verbal instructions while you are lying down that guide you to relax all parts of the body and eventually withdraw from all senses.

Our senses allow our external world to enter our internal, whether it be sounds, textures, smells or sights. When we are detached from these senses we can observe the mind without the distractions of the external world.

6. Dharana – concentration

Dharana means one-pointed focus, or concentration. Once we are no longer pulled this way or that by our external senses, we can focus the mind on one place, object or idea.

The chances are that when we talk about practicing meditation we actually mean dharana. This practice can mean focusing on the breath, sound, mantra (whether silent or spoken), a particular chakra energy center or even visualizing an image, symbol or deity.

By focusing on one thing, we can slow down the mind and thought process, which prepares us for meditation itself.

You might also like: What Are The Chakras And Kundalini Energy Flow? Here Is My Complete Breakdown [VIDEO]

7. Dhyana – meditation

Dhyana is the meditative state that spontaneously comes from long practice of dharana. We may experience this for as little as a few seconds or even up to 20 seconds in a half-hour or hour-long dharana practice.

In the meditative state of dhyana, the mind becomes so still and aware that there are few or no thoughts at all. Of course, this takes many years of practicing all of Patanjali’s limbs. It is worth reminding ourselves that it is called yoga practice for a reason and the path is the practice!

8. Samadhi – bliss or enlightenment

The word samadhi is one many of us have heard of or are familiar with. Samadhi refers to a spontaneous state of bliss or enlightenment that is the final goal of yoga.

It’s not something we can just will to happen, just like falling asleep at night. It just happens.

When a yogi has spent a long time in a meditative state and their inner being is in a permanent state of dhyana, they will experience samadhi. The meditator merges with the object of its focus, feeling a connection with the divine, all living beings and the universe.

It is the ultimate goal of yoga, finding that connection with universal consciousness.

Patanjali’s Ashtanga Yoga is not a checklist to be completed in a specific order, as much as the do-ers in us would like!

In reality, all limbs must be practiced together with equal importance. The yoga sutras offer the framework and wisdom for those wanting to walk this path and it really is applicable to everyone.

By letting the yamas and niyamas infuse in our daily lives, we bring our yoga practice off the mat and out into the world. This dharma mittra combined with regular asana, pranayama, and meditative practices can help us build and welcome more balance, joy and peace into our lives, just as Patanjali’s ancient manual describes.

You can expect any yoga teacher training course to go over all eight limbs of yoga in great depth and then talk about ways that we can follow the path in our daily lives. If you’d like to explore these limbs with me, then join me for a tour of my YTT program.

Next Steps

- If you’re interested in learning the three skills that empower you to embody your yoga off the mat to get the results you desire in your personal life, check out my Yoga for Self Mastery course.

- Explore my knowledge hub for How to Become a Yoga Teacher or consider becoming a Somatic Yoga Coach in my newest certification program.

- Practice yoga with me on my YouTube channel with over a thousand free classes.

Experience 3 Training Videos from Inside My 200-Hour Online YTT

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

- What is Kriya Yoga? The Philosophy and Practice

- Uddiyana Bandha: Tapping Into Your Deep Core

- 4 Reasons Hasta Bandha Is Essential To Your Yoga Practice

- Vitarka Mudra: What It Is and How Do You Use It?

- Shakti Mudra: What It Is and How Do You Do It?

- Garuda Mudra: What It Is and How Do You Use It?

- Kali Mudra: What It Is and How Do You Do It?

- Shunya Mudra: What It Is and How Do You Do It?

- Varuna Mudra: What It Is and How Do You Use It?

- Vayu Mudra: What It Is and How Do You Use It?

- Samana Vayu: The Energy of Balance & How to Access It

- Apana Vayu: The Energy of Release & Surrender

- Udana Vayu: The Ascending Wind

- Prana Vayu: The Breath of Vitality

- Vyana Vayu: The Energetic Secret to Flow

Learn how to do 11 of the most popular yoga poses correctly. Free video + PDF download.